Yasaman Moussavi holds an MFA with two emphases on Painting and Printmaking from Texas Tech University, where she explored and developed her skills in papermaking, printmaking, and installation art. She also holds an MA in Art Studies from Tehran University and a BFA in Painting. In her art practice, she explores the socio-cultural in-betweenness as a capacity and disposition to participate in meaning-making across cultures and languages. For her, transitional spaces are the performative embodiment of spatial mapping and in-betweenness. Her works have been displayed in many national and international solo and group exhibitions. She has been a member of the Spudnik Press Exhibition Committee since 2017. She is a co-founder of Didaar Art Collective, a Chicago-based Iranian art community. Yasaman currently lives and works in Chicago.

Yasaman was interviewed by Aidan Ciuperca as part of his Spring 2020 Internship at Spudnik Press Cooperative. Aidan is a printmaker pursuing his BFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Aidan Ciuperca (AC): How would you describe your practice to someone who has never seen your work before?

Yasaman (Yasi) Moussavi (YM): I’m interested in concepts of space and place, and how these two things convey a common kind of experience. Place can be defined as where we physically live and where we find security, but space is more of a subjective kind of experience about sensation and desire. For instance, in my recent work Intervals, I explore creating the sense of space through architecture and linguistic structure. My goal was to make sense of the feelings we have when we are in a place and allow it to be experienced through a tactile material like paper. This is a subject matter that’s not tangible, so the materiality is important in order to make sense of those feelings.

AC: What led you to working with printmaking and papermaking?

YM: When you think about traveling through places, you are in between two different locations. The important part of that experience is not where you start or where you want to end up. It’s how you move through the space, what you are experiencing, and all the steps you take. Printmaking and papermaking both have those technical and psychological qualities, which is why I started using them. When I studied in Tehran, Iran, the education was focused on the academic study of figurative painting and drawing, but when I traveled to the United States, everything changed. I started to think about the ways the material I work with can be important in the process, and in the creation of the material.

Intervals Installation at the Beverly Arts Center

AC: How does your work with printmaking and papermaking connect to installation?

YM: The shift in my work from 2D to 3D is tied to the way my life changed when I moved. I initially moved to Lubbock, Texas in 2012 to get my MFA at Texas Tech University, but in 2014, I returned to Iran for six weeks before coming back to continue my education. I went to see the traditional architecture in Isfahan, where my dad is from. There is a mosque there that I visited many times as a child called Sheikh Lotfolah. It has a narrow hallway with windows that bring light into the space. As you walk through that hallway, all of a sudden you see that a bigger space opens up to you. When I experienced that transition, I felt like there was something more than just the patterns, the colors, and all the interesting details of Islamic art. It’s not about that anymore. For me, it was about something bigger than myself, something that I experienced by moving through that space. That was the moment that I felt like painting just wasn’t something that could share that experience with my audience. In the same year, I was lucky enough to experience another architectural space: James Turrell’s Breathing Light at LACMA. I went into the space and there was nothing there but light. In that moment, I experienced a feeling similar to what I discovered at the mosque. These two different kinds of architectural spaces and places got me thinking about creating something that’s not just about the visual work, but about that experience.

Shadow Facing the Light Installation at Texas Tech University

I ended up making my first installation piece called Shadow Facing the Light as part of my thesis for my MFA. For about a year I was drawing and painting on big sheets of paper, about 6 feet to 8 feet tall. In the installation, I played with the effects of light on engraved plexiglass and copper plates to build the space. When you asked about how my work changed and how I transitioned from painting to installation-based work, it was because I started to think about what I’m experiencing right now and how I want to share it with my audiences.

As for my relationship to printmaking, I started to explore the process more during my MFA. During my last year I was making drypoints on wood and thinking about the process of the work. I started working on wood because, at that time, I was thinking about the effects of nature and its networks. As I created those drypoints, I started to think that I wanted to use the plates as a work of art because all the steps in printmaking are also part of the work. So, I started to print from the plates and then use them in my installation. I would cut them, shape them, and color them to create a new space. The Passengers Series, created from my wood drypoints, is all about the process of the work, nature, and how I can make use of the cliché of printmaking, the blocks, as a work of art.

Passengers Installation

AC: What part of your work do you find most fulfilling?

YM: The most important and fulfilling part of the work for me is when I am creating and developing the work. It’s that process of thinking, producing, and critiquing yourself that is really enjoyable for me. Because sometimes I’ll discover something in my work that wasn’t intentional, and it surprises me! For instance, last year when I started to work on the Interval Series, I was making large papers at Spudnik. I wanted to build big sheets, but it was really hard sharing the space with other people, not having the studio for yourself. As I started to grow, I started to consider how I should handle this situation and discovered something new about the process of the work. I was thinking about the central courtyard architecture of the 17th-18th century in Iran and the family house in Isfahan. But when I started to make them, I faced challenges with the space that I was working in. It even changed the way that I was thinking about the place in space.

The other important part is when you see your work, as you visualize it, in the gallery space. That is really, really enjoyable for me especially because I don’t have a studio right now, and as an installation artist, it’s very hard. I have a corner in my house where I work, and if you come to my house, you’ll see that that corner is just covered in nails. I have been making small maquettes of my work and then nailing it to the wall. I think that it’s hard for me to experience and explore the space in the smaller version, but it works.

AC: The way you’ve been working in this corner of your house brings up the issue of how artists have had to adapt to making work at home because of the pandemic. I was wondering if there were any skills or hobbies that you’ve been working on.

YM: The corner has been getting too crowded because of the pandemic, because before that I went to Spudnik and I made work there. But now during the pandemic I haven’t had that chance, so I started to work with the paper and stories that I already have. I’m working on a series of small squares made from scraps of my handmade paper. As each day passes, I take one of those papers, pin it to the wall, and another one, and another one. They’re getting really thick and they’re getting really big.

I also started to read more in my own language: short stories and my great grandparent’s diary. When the pandemic started, each week I would read two short stories with a group of colleagues. I started to use them in my work: the sentences, the words, what they mean. I started to analyze how I can use them, how the structure of the language can relate to the structure of the work that I’ve created. I started to ask questions and explore Farsi and English and how language creates a sense of communication. In a pandemic especially, you don’t have the kind of social connection that you find physically in an environment. You experience it differently in virtual spaces like Zoom and also in writing, like texting your friends or writing for yourself. We are exploring and experiencing an era that is making history. All of these things for sure have influenced me and my work. At the same time, it’s really hard to think and work, so for me all of these are sketches and questions.

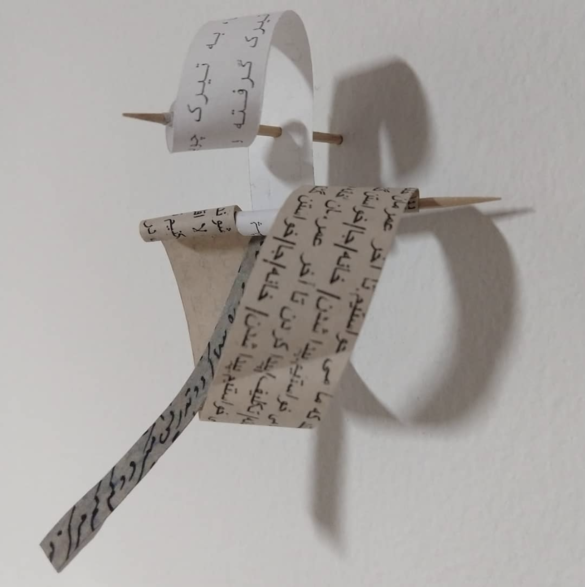

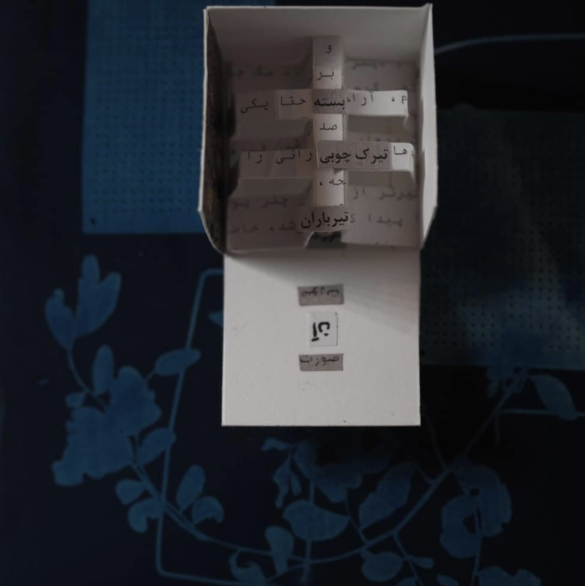

“Constructing space through words, sentences and written forms” work in progress from Instagram

AC: Yeah– like the work on your Instagram!

YM: Yes! Let me explain the process of the work. I’ll read a story, short stories or even my own journal or my grand grandparent’s diary. All of those stories are interesting, but sometimes I’ll just have a feeling with a word or sentence. I’ll think about it more, about the letters, about the meaning of that word, about its different meanings in other languages. It’s all about the communication, how you communicate through words, how the words and sentences work for me and what the difference is between visual images and text. Working with text, especially text that other people are not familiar with, is really, really risky because people might just pay attention to the aesthetic beauty of it. I used Farsi text because it is my first language, therefore I have a deeper understanding of it in comparison to English. Through the process of my work, I analyze the words by deconstructing them, breaking them down into pieces, and then putting them on different supports. Sometimes the support is handmade paper made out of hundreds of pieces of scrap paper, sometimes it is the wall, sometimes it is a handmade book, or sometimes it is the printing block itself. For me using language is a form of research.

“Exploring the sense of space and place through architectonic and linguistics structures” from Instagram

AC: Didaar is a Chicago-based Irainian arts collective. How has being a part of that community influenced your work?

YM: The aim of Didaar, meaning meet-up in Farsi, is to create communication and cooperation between Iranian artists and those active in the field of Iranian arts. Relying on the exchange of experience with and reflection on modern and contemporary art, Didaar’s goal is to help with professional development, both in art theory and practice, by promoting art-related discussion and criticism. On the last Sunday of each month, we have a lecture and discussion series. Currently, we have had four sessions in which we focused on the concept of trauma in contemporary art. We started to discover and explore this concept when the pandemic started in March. This series is continuing through November. You can find the details on Didaar’s website.

AC: Outside of the pandemic, what kind of work happens at Didaar? Is it a studio space? Is it more of an artist social space?

YM: We started Didaar in my friend’s studio and from there, we started to critique the works of artists. After that, we started to grow and think about what we wanted to discuss and explore together. For instance, we talked about art and business, art and social media, along with many concepts and questions about contemporary art. We had a really big event last year in partnership with the MCA, in which we celebrated the life of a well known director, Abbas Kiarostami. For that event, we curated the work of Abbas Kiarostami’s students and screened three of his pieces. That was a really big milestone for our group. The MCA was really supportive of the Iranian community and we have started to work together more. Other than that, we create platforms for Iranian artists, like with our recent open call. We just finished accepting work with a focus on drawing and printmaking. We asked participants to submit their work and we challenged them to explore space, what space means for them, and how they explore that concept through two-dimensional techniques. The exhibition is going to be in April 2021, with a local gallery in Chicago, Oliva Gallery in West town. It was great to see the work of Iranian artists here in the United States, here in Chicago. This will be the first chapter of this exhibition and we’re going to have more chapters in the future. Another part of the work at Didaar is the discussion sessions we host on Instagram, which are in Farsi, interviews with the artists and curators, and so on and so forth. We also have a website, which has created a platform for art historians and people who want to write about art share their articles and ideas.

AC: I think we got to everything. The only thing that I wanted to ask more about because of personal interest was your book series Seed Stories.

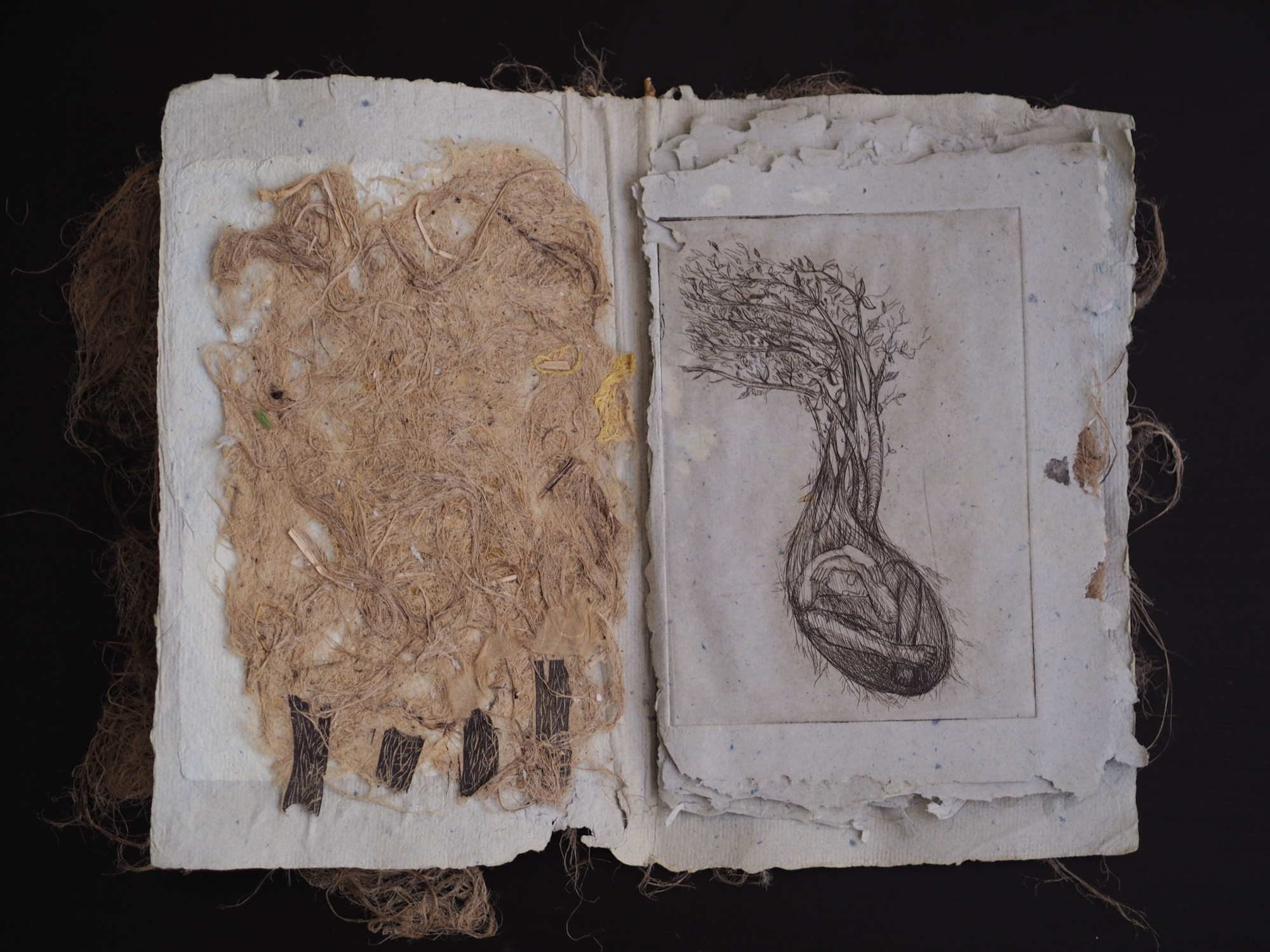

YM: Seed Stories was something I made at Spudnik during my residency. When I moved to Chicago, I lost the community I had in Texas. It felt like another immigration, but something that really helped me find myself was nature. It made me think about nature as a source of my work and I started to create the book series as a component of my exhibition Roots. The thing that influenced my decision to work with stories of life and death specifically was losing my grandmother. She was the person who taught me about traditional literature in Iran and she also had a really green thumb. In my Seed Stories series – one is an accordion book and the other one is made from kenaf and handmade paper – all of the images are related to the concept of origins, creation and the cycle of life and death. These works are really small, and I enjoyed making that space and the work was so intimate for me. Those very private and intimate moments are experienced by the audience as they pass through the pages and feel the tactility of the paper and the smell of the paper. It was a different way of creating space on a much more personal level.

Seed Stories – made at Spudnik with kenaf and handmade paper

Copies of Yasaman’s accordion book Seed can be purchased through Spudnik for $10.00.

Keep up with Yasaman on Instagram @yasi_moussavi and check out her website. More information about events and discussions at Didaar Art Collective can be found on their website and on Instagram @didaarartcollective.