Lisa Glenn Armstrong is a multi-disciplinary designer, artist, and educator living in the Humboldt Park neighborhood in Chicago. She received her MFA in Motion Graphic Design from California Institute of the Arts in 2018 and her BFA in Graphic Design from DePaul University in 2012. Her work focuses on themes of movement, time, and the tensions between artificial and emotional intelligence. She currently teaches motion graphics in the School of Cinematic Arts at DePaul University and is part of an electronic music ensemble called Chandeliers. She was also recently a Spudnik fellow.

Kirsten Holland: How did you get into printmaking?

Lisa Glenn Armstrong: Well, I studied graphic design in undergrad and grad school, and I got really into screenprinting at CalArts (California Institute of the Arts), which is where I went to grad school. They have this long history of printmaking in their program, and this kind of beautiful, but a little decrepit, print shop. I just kind of fell in love with working in there. It changed the way that I worked and thought about designing things.

KH: How do you feel it changed the way you worked and thought?

LA: I think a lot of times, things are really kind of hands off in design schools today. In my undergraduate experience, we didn’t do any screenprinting. We did digital printing for posters, but even then we weren’t always required to print them. So being able to pick out the inks, design within constraints for silkscreen, and then actually physically print it—something that you designed—yourself was this sort of empowering feeling. It can be frustrating and time-consuming at times, but it’s a very rewarding process. And, since it’s actually made by hand, you get a very different look and feel that I think people now really appreciate. You can see the mistakes and the texture. There’s more of a human touch that’s evident that is lacking when I print things digitally.

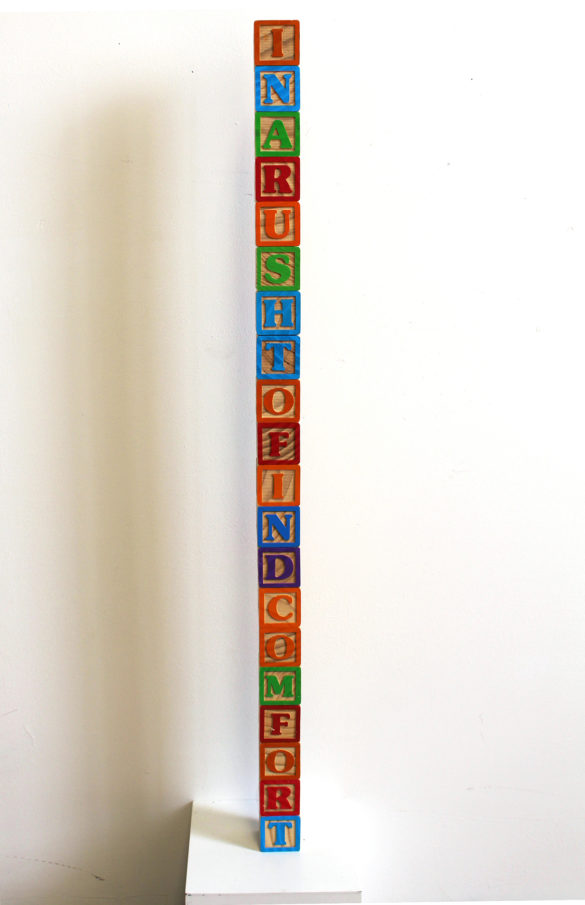

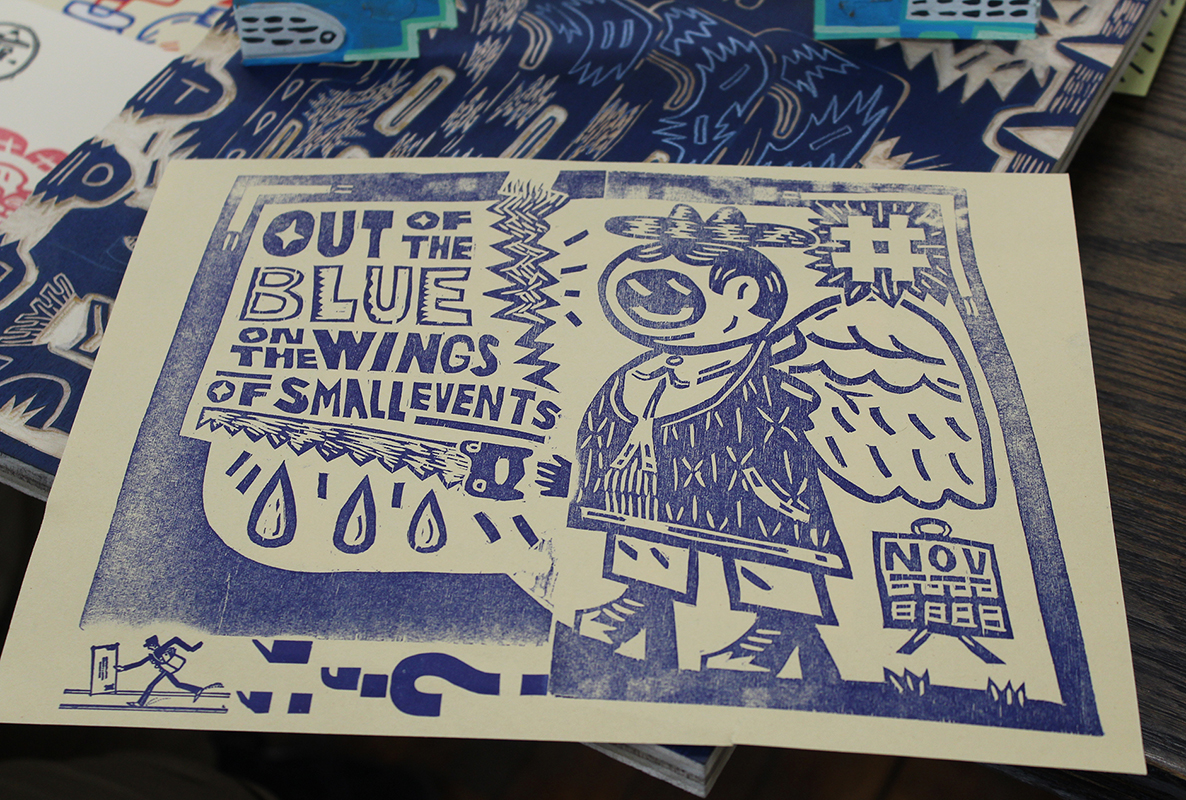

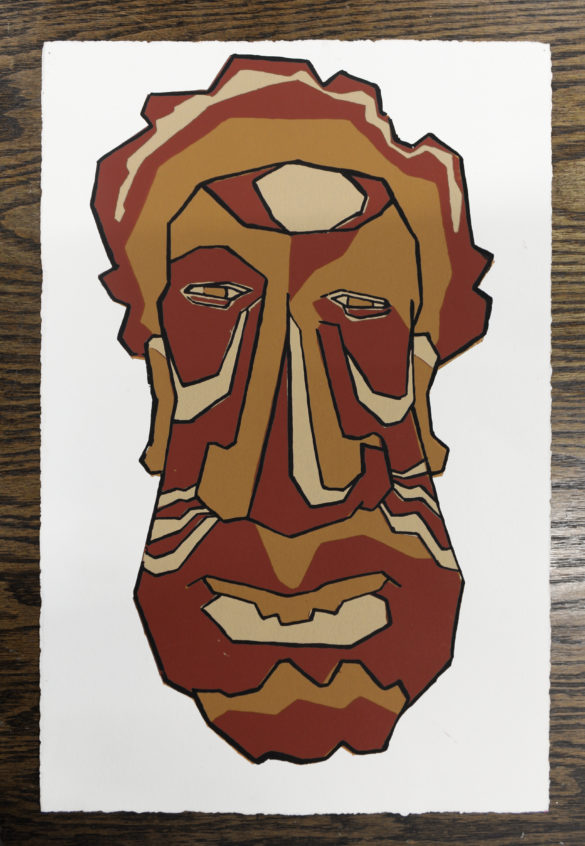

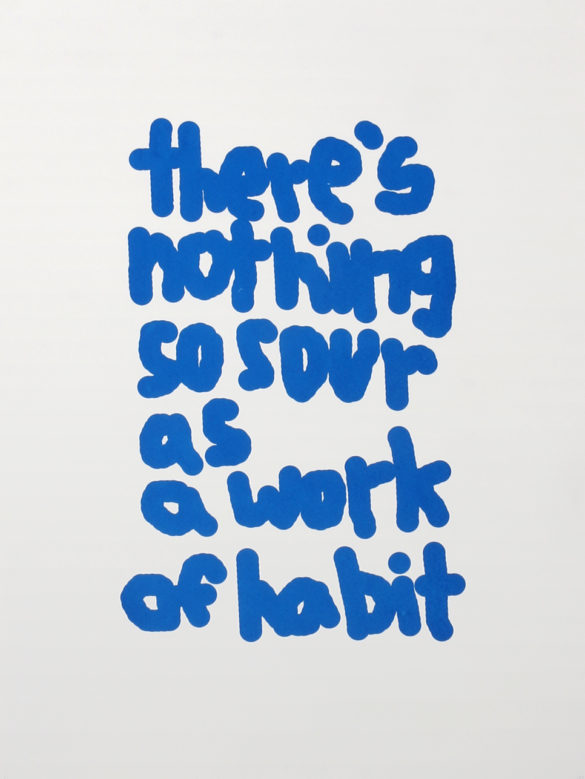

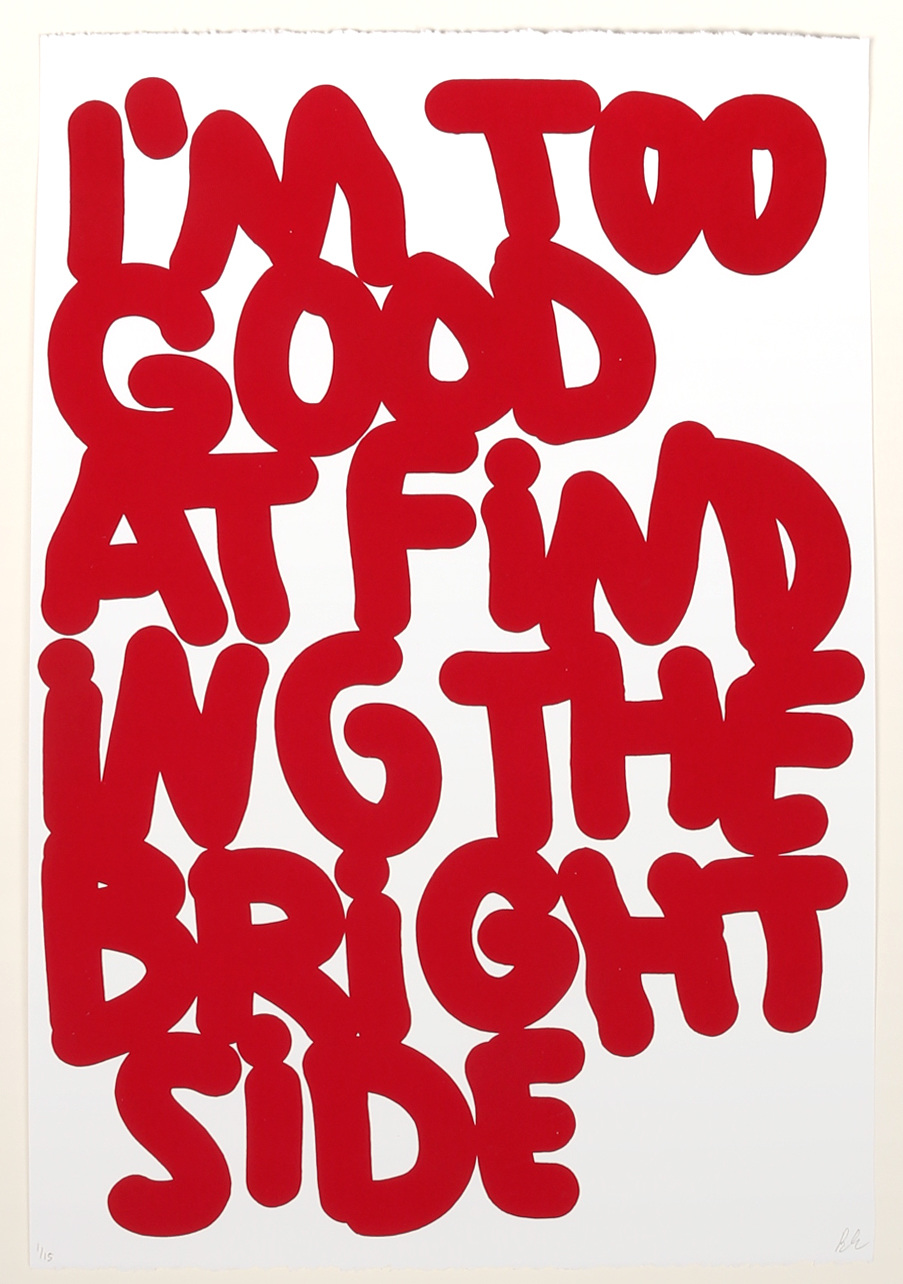

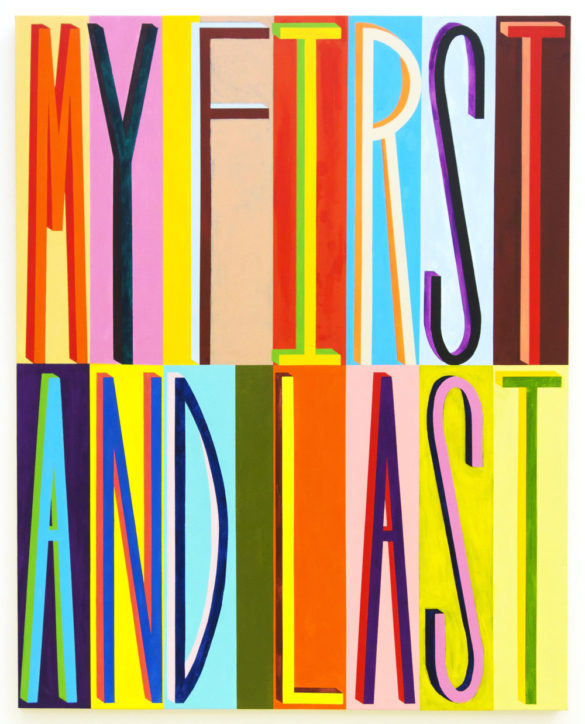

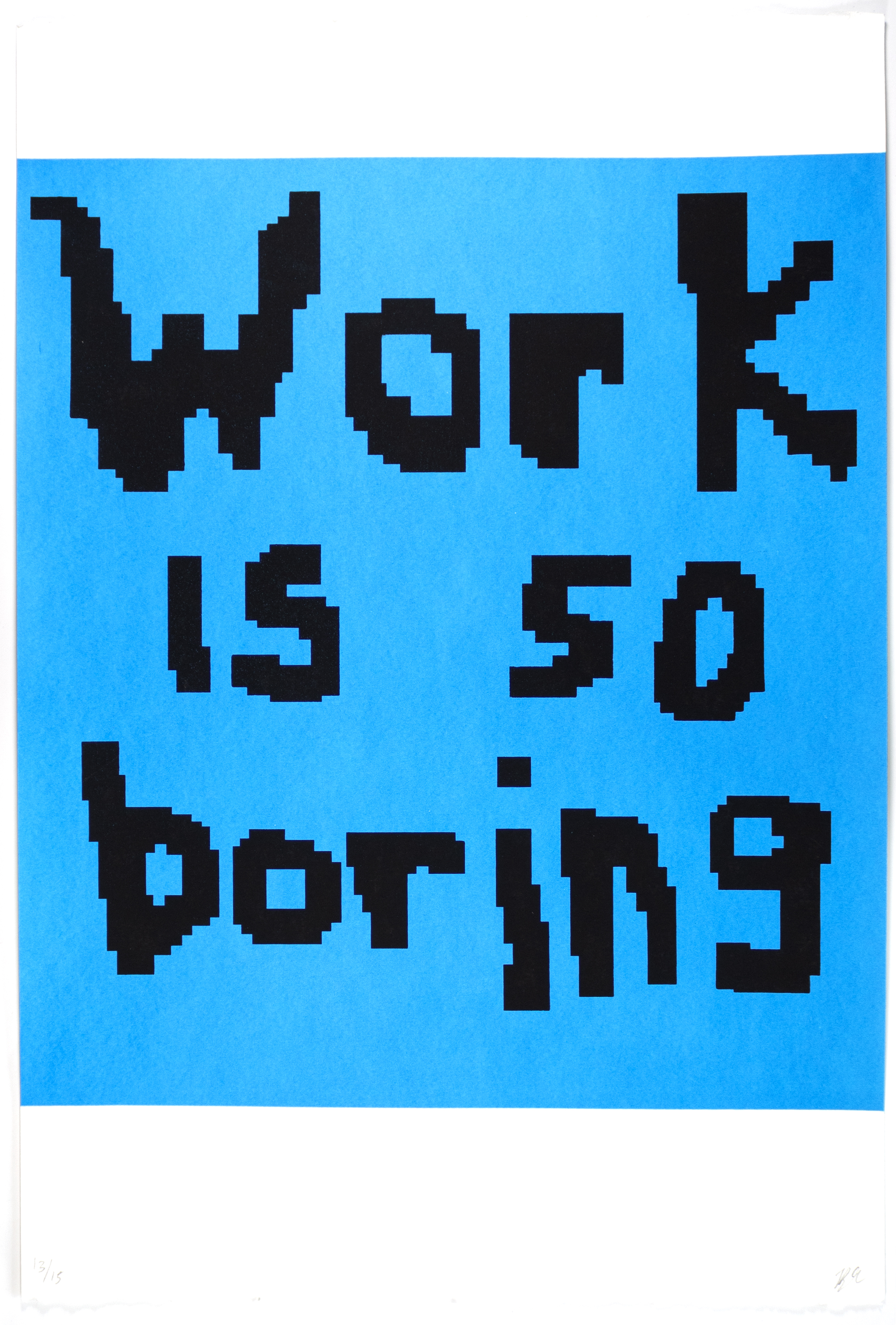

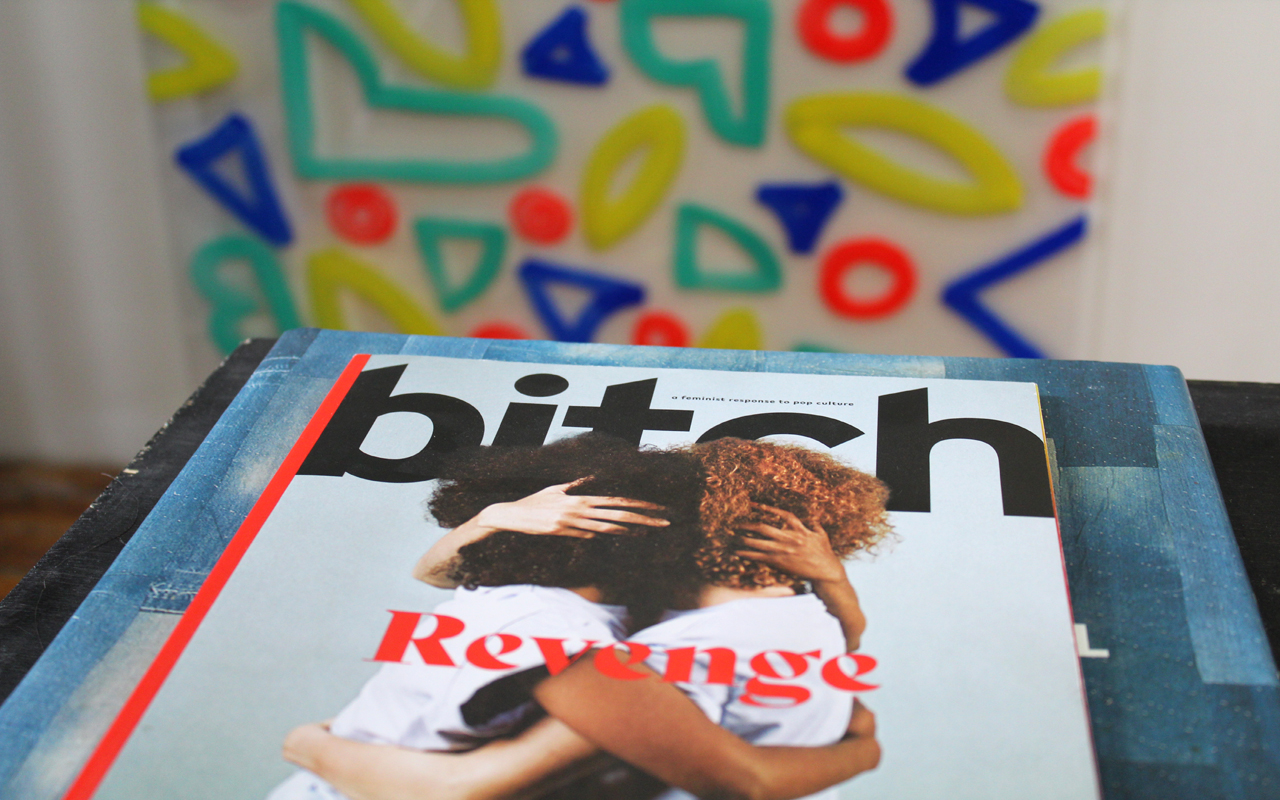

A collection of Lisa’s prints.

KH: Do you have any favorite mediums that you’ve tried so far?

LA: I mostly work in silkscreen and risography, but I’ve also done some relief printing. I don’t have a favorite necessarily, but I would say that I do silkscreen and risography the most. And there are different things that I like about those two. Risography is the cheapest form of printing. You get those amazing fluorescent colors that are harder to achieve and retain with silkscreen. So, it’s a great way to produce things quickly and cheaply. And, silkscreen… it’s just fun (laughs). It’s just fun to do. If I haven’t done it in a while, I feel like I am missing out and I’m not working that part of my brain. But I also carved a lino block recently, and it was really satisfying to spend a couple of hours carving away at something. So it just kind of depends. I would love to get into etching at some point; I haven’t done anything with that. And letterpress is really high on my list of things that I want to try next.

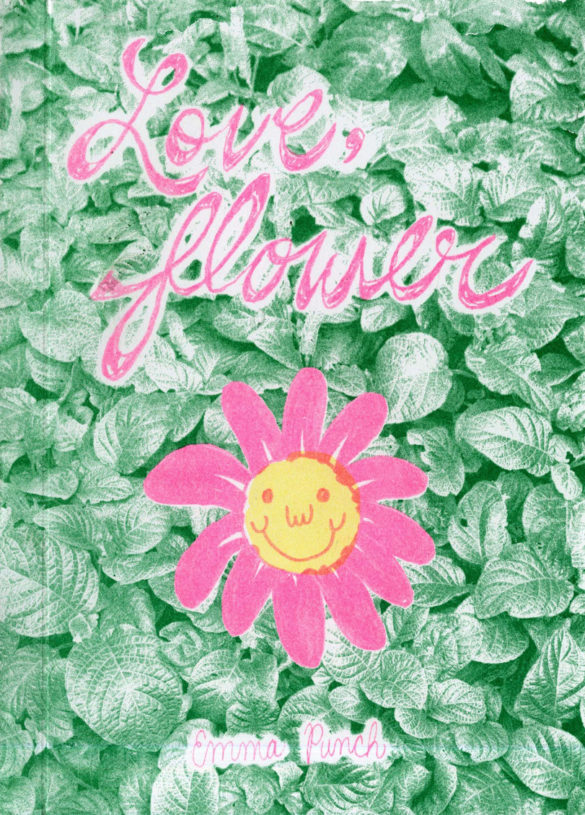

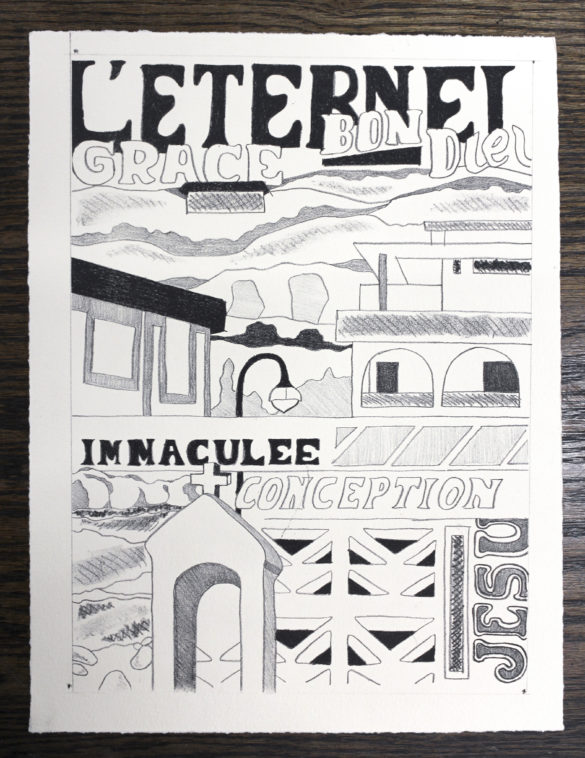

Einfühlung I, risograph print, 2019.

KH: We already touched on this a little bit, but how do you feel your work in print relates to your more digital work in design and motion graphics? Do you feel that they inform each other or intermix at all?

LA: Yeah, I’ve been working on this short animated film about that pretty much since the start of the fellowship. It was a response partially to teaching motion graphics at DePaul. I was also just thinking about how much time I spend on the computer for my own work, and how much ownership I can claim over that work versus an algorithm. So, I decided that I wanted to take these things that I was designing and building (digitally) in 3-D and translate them into print, and then bring them back into the computer so that there’s kind of this feedback loop between the digital and the analog and back again. A lot of that is just sort of trying to bring some of the humanity back into the work, because when I look at 3-D rendered work it sometimes feels cold or austere. And, there’s something that happens when it goes through the riso that gives it this sort of like warm, grainy, tactile feel to it, almost like 16 mm film. And of course, there are mistakes that happen along the way. So, a lot of it has been kind of experimenting with the mediums to see what happens. Now I’m trying to organize it and put it all together into a finished thing.

Frames from risograph-printed animations, 2019.

KH: Do you have any other current projects on the horizon besides that one?

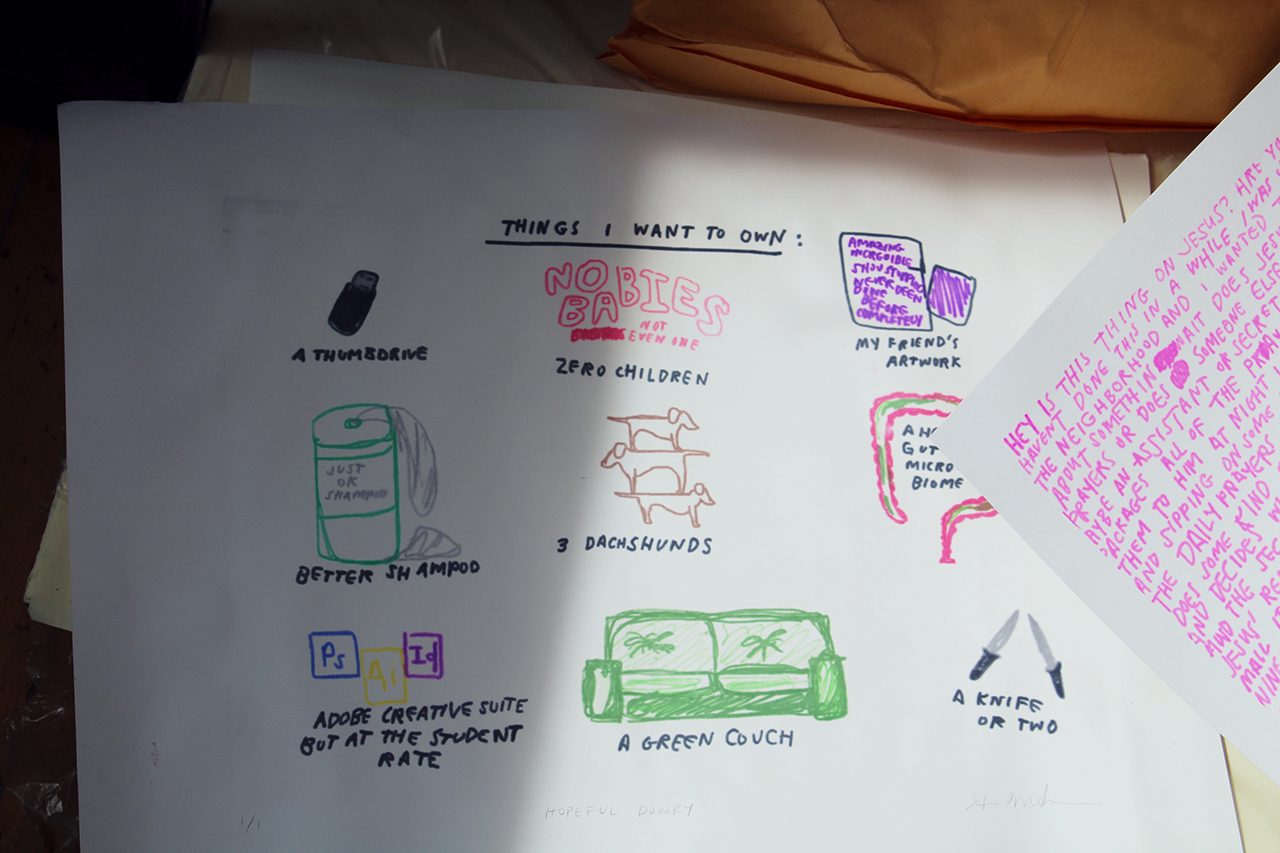

LA: That’s pretty high on the list, but I also started making a book last week when I was in California with some of my friends from grad school, and it’s inspired by Sister Corita Kent. We were looking through her book, Learning by Heart, which is something that has informed a lot of my work, and so has her teaching and her work in general. We decided to create these assignments based off of her book, and make a book of those assignments that we followed through ourselves and then documented, showing the outcome of what you could do with it. So that’s being pieced together and hopefully printed soon. I also want to do a curated artist’s book. I would put out an open call for submissions, loosely around ideas of the paranormal and metaphysics, and get people to contribute their alien encounters or ghost stories. Then the plan is to donate whatever proceeds are made from it to the ACLU. I’m still kind of working out the prompt and everything, but I think it will be a risograph printed book. There’s a lot of aliens and sci-fi throughout what I do.

KH: Would you say that you are inspired by aliens and sci-fi? Or how is that integrated throughout your work other than the curated book you just talked about?

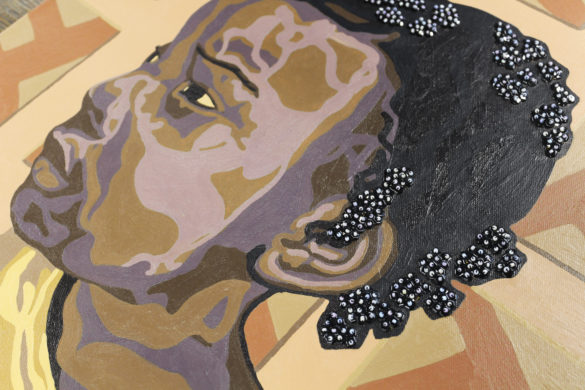

LA: In a lot of my work, I take inspiration from books and text, like how I mentioned Sister Corita Kent. I read a lot of kind of new-age-y, almost self-help stuff, but also a ton of science fiction, especially feminist science fiction. So, I love Octavia Butler and Ursula K. Le Guin. I love science fiction as a tool for thinking critically about the conditions of the world that we’re living in now. It gives us this critical distance and space to think about what else might be possible. Or, if we continue down on the road that we’re going on now, where will that lead us? As a designer that is interesting to me, to think of how you can structure or think about designing for the future. There’s definitely an interest in asking questions, thinking about the unknown, and thinking of things as fluid and relative rather than binary and black and white. A lot of the text in my cards and things that I was printing came from Octavia Butler and another writer named Adrienne Maree Brown, who basically researches Octavia Butler’s work and writes about it too. There are a lot of interesting ideas specifically in Octavia Butler’s work about adaptation and social change, and those are all interests of mine.

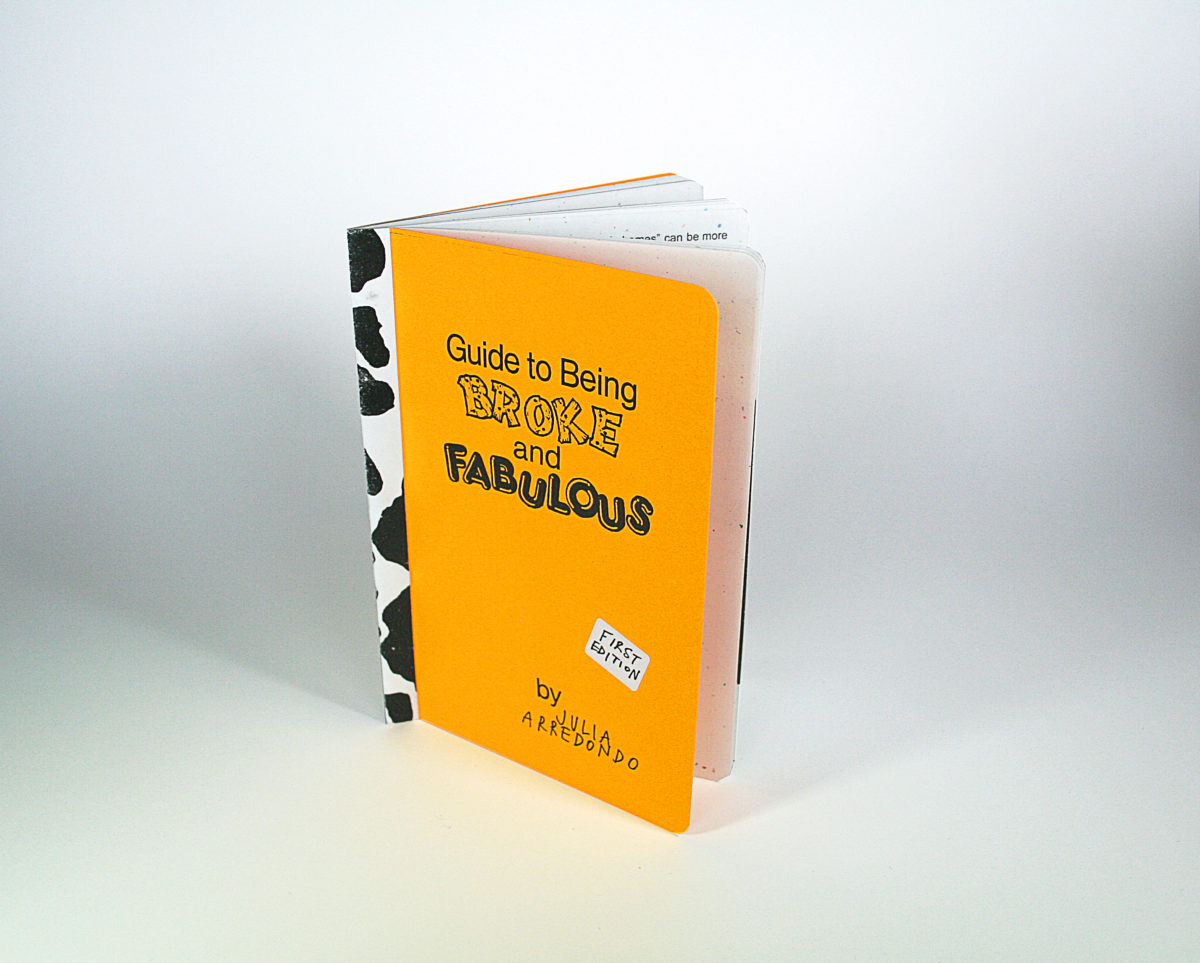

To Create is to Relate, risograph-printed miniature poster and artist book, 2019.

KH: Switching gears a little bit, what sort of directions to you see your work going in the future? Or do you have a particular direction you want to head in?

LA: I want to just try to remain open and adaptive to whatever comes my way. I try not to get too set in working in one particular way. The nature of working in design especially is constantly changing, so just being able to be open to either working in a time-based medium, or print, or something else is really important. I’d also like to do more teaching, and use that as a way to complement my practice too. There are also just a lot of things I want to learn how to do. I want to copper plate etching, but I also want to learn 3-D sculpting software. So I have interests in very different realms, but I’m interested in how those might inform each other.

KH: You’ve talked a little bit about how you also teach at DePaul, and want to teach more as a part of your practice. What has your experience teaching been like, and how does it inform you?

LA: It’s been great, and challenging, but I feel like in the back of my mind I always knew I wanted to be a teacher. All of the sudden, I just decided, “Okay, I’m going to do that thing.” So it feels right, I guess. I’m happy in that role, and I love that my job is to be excited about something and get other people excited about it. And, it could be, you know, changing a tire or something. I’m just happy to be in that kind of environment, sharing ideas and getting people to think about what they’re interested in. It’s inspiring to see what people are making, what they’re thinking about, and to see the kinds of patterns across too. The common themes are interesting. This is also my first year teaching, and so, it’s been good.

KH: You also recently finished your fellowship at Spudnik Press. What was that experience like?

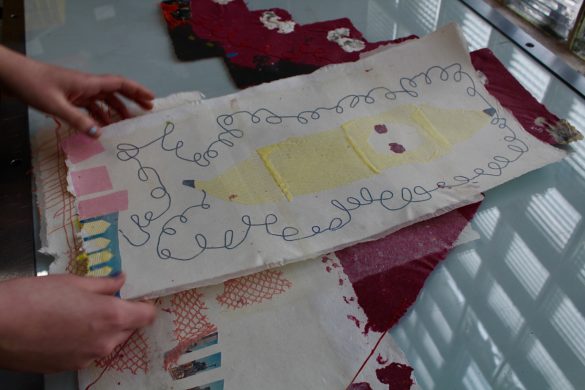

LA: It was really nice. Because I had just moved back here from California a couple months before starting, I was really looking for a place and a community of other creative individuals to fall into. I think I was really lucky with the group that we had too. We all just clicked really well, and had similar interests. I think my favorite thing was the public program we did. We did a workshop called Paper Trail, where people came and tried out different printmaking techniques, and it was just a lot of fun to do. All of the planning leading up to it and working with the three other fellows was really nice. It’s also just been good to have access to the studio and be around other artists, to see what they’re doing and get feedback on what I’m working on. It’s a motivating environment where you encourage each other. So yeah, that’s been really nice.

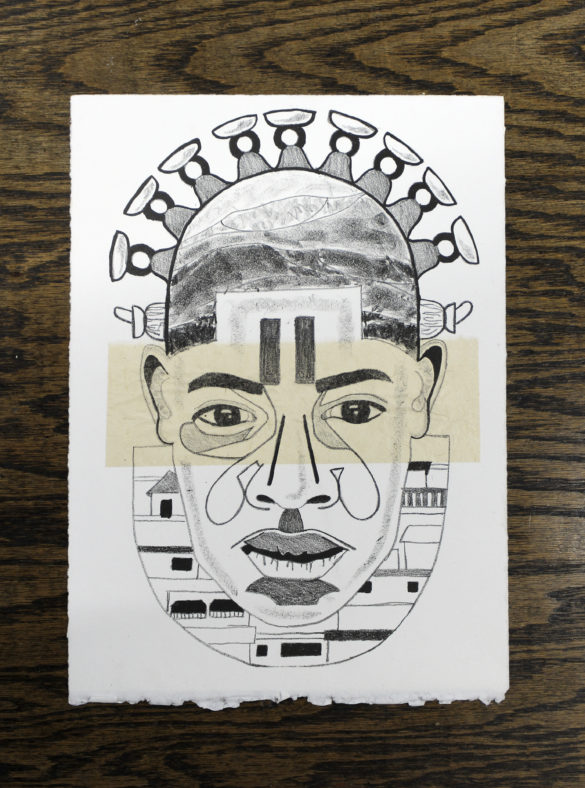

Einfühlung II, risograph print, 2019.

KH: We’ve been talking a lot about your work, so I have one more question that’s more just for fun. What do you do when you’re not making art or designing? Do you have any other hobbies or interests?

LA: Yeah. I like to ride my bike. I like to watch sci-fi movies, and read sci-fi books, and just watch lots of movies in general. I’m also just trying to get outside as much as possible, and enjoying that it’s not ten degrees outside right now. I think moving around is how I get ideas and work through things, too. I like to try and travel if I can. I have family in North Carolina and two little nieces, and I like to go visit them every once in a while. And go to art shows, museums, and galleries, and stuff like that. And I play in an electronic synth band too.

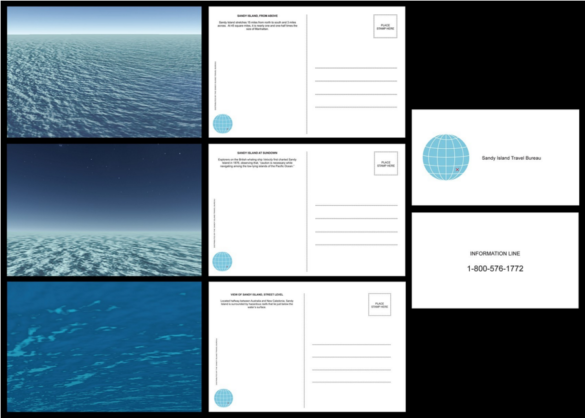

Zeta Reticuli Incident, risograph-printed artist book about Barney and Betty Hill’s 1961 alleged UFO abduction, 2019.

To learn more about Lisa and see more of her work, you can follow her instagram @liselefteye or check out her website.

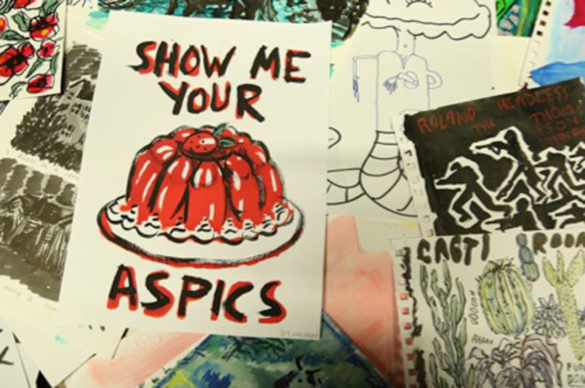

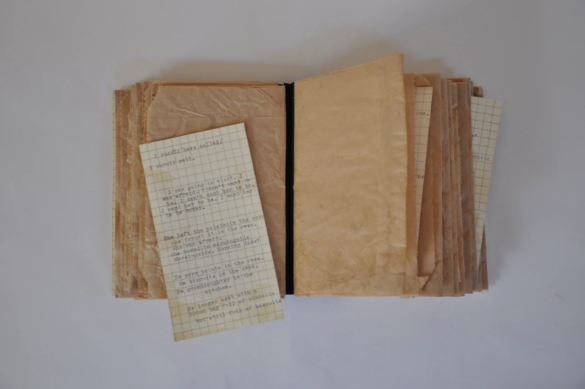

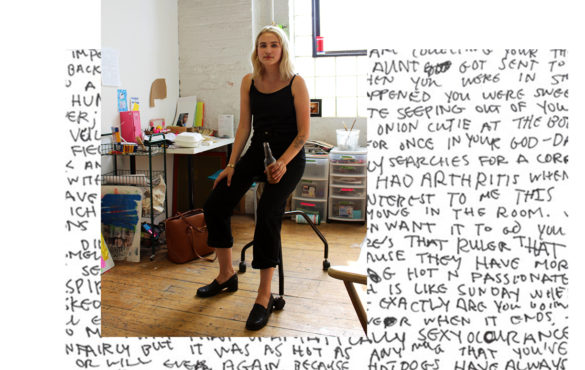

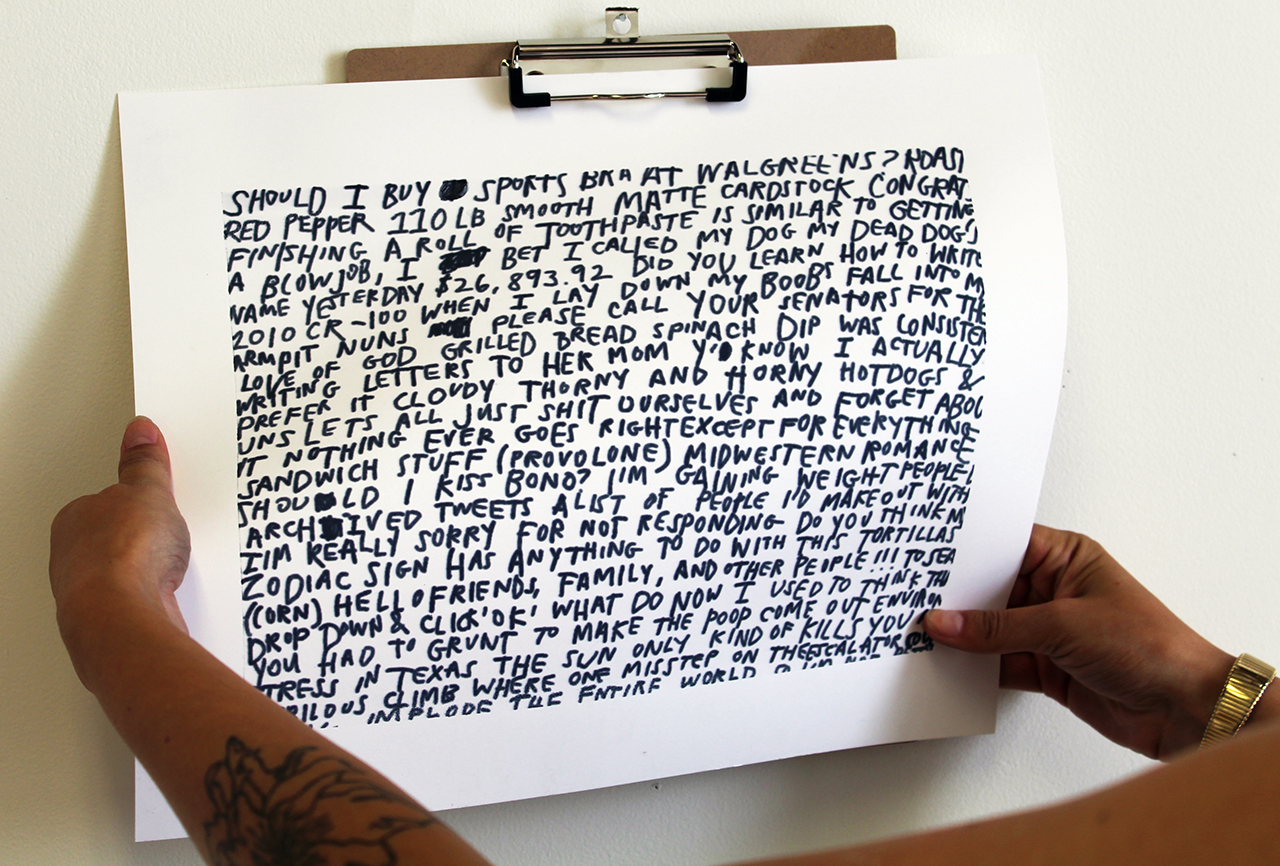

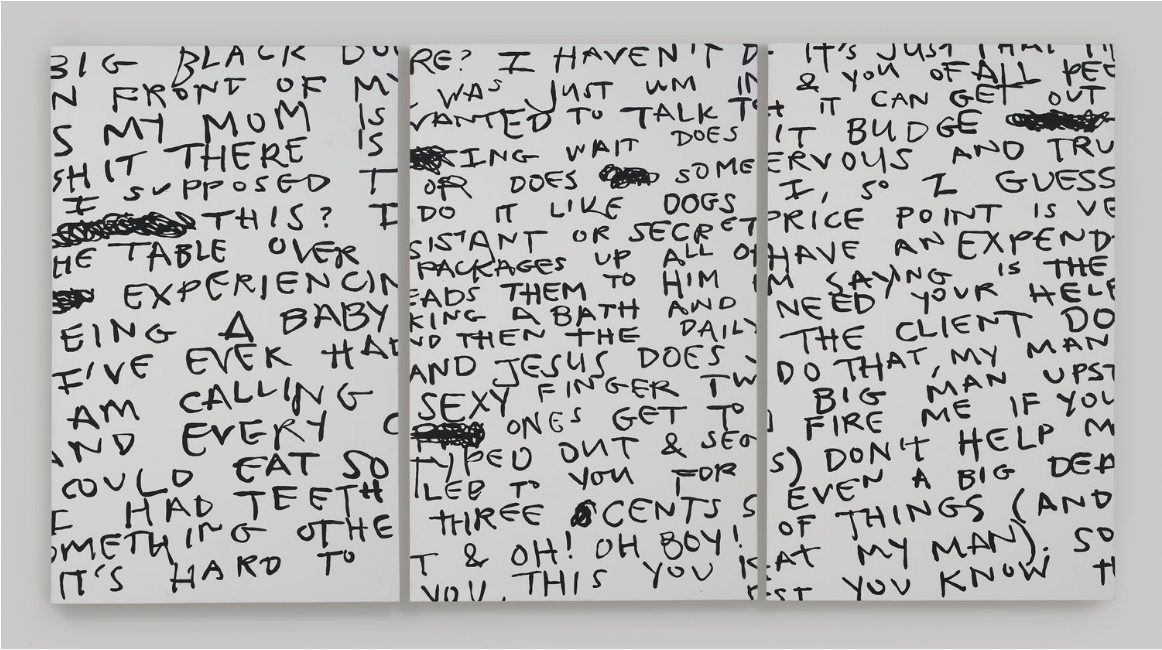

I had been doing the @polenta_girl thing, which is my drawing project and I had been trying to figure out how to move forward from there. It was not serving me anymore, so I started thinking more about writing as a practice, and then I made this print during my fellowship, which perhaps is nothing and everything at the same time?

I had been doing the @polenta_girl thing, which is my drawing project and I had been trying to figure out how to move forward from there. It was not serving me anymore, so I started thinking more about writing as a practice, and then I made this print during my fellowship, which perhaps is nothing and everything at the same time? I was really interested in exploring the finality of the monoprint in congruence with the finality of language. I started writing, and if I messed up I had to scratch it out and keep writing and writing and I did it all in one take.

I was really interested in exploring the finality of the monoprint in congruence with the finality of language. I started writing, and if I messed up I had to scratch it out and keep writing and writing and I did it all in one take. LJ: As a viewer, it’s such a natural response to want to be able to finish the sentence, to figure it out.

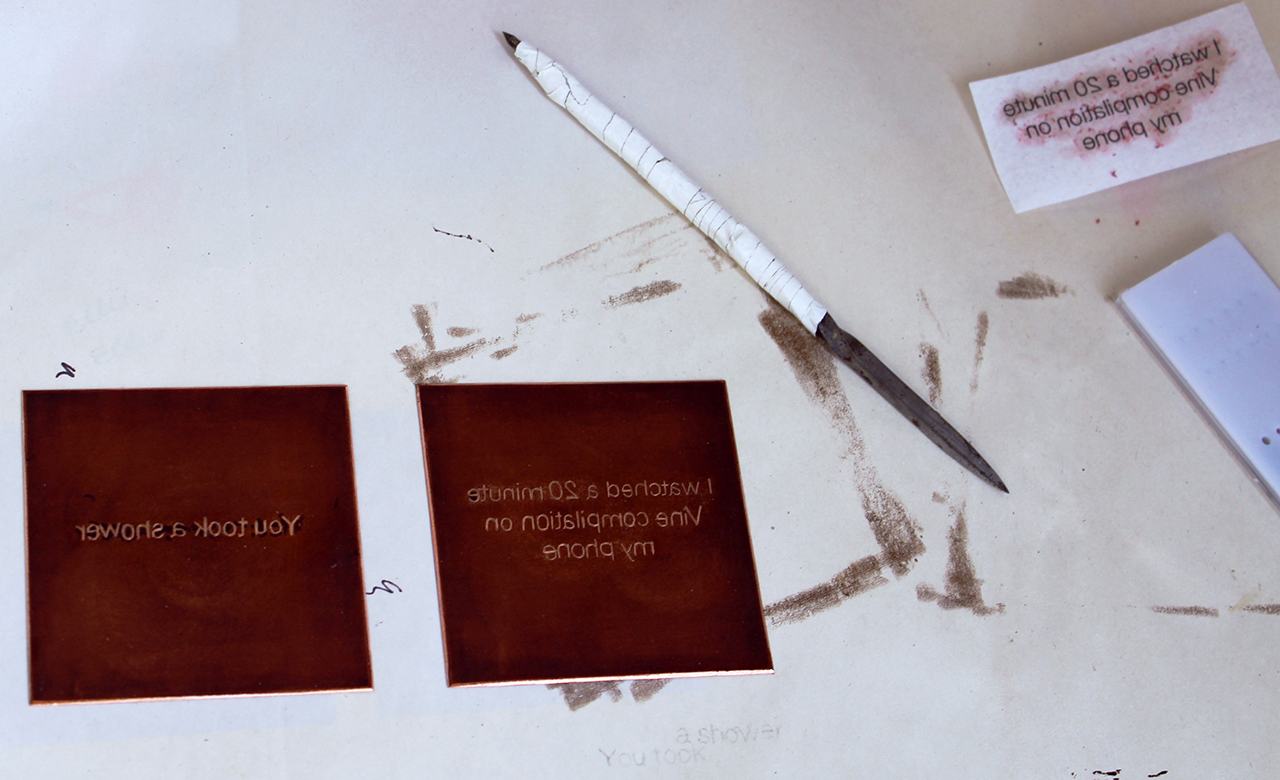

LJ: As a viewer, it’s such a natural response to want to be able to finish the sentence, to figure it out. LJ: Why is it important that you replicate the font by hand?

LJ: Why is it important that you replicate the font by hand?