Andrea Carlson is a visual artist from Grand Portage, MN currently living and working in Chicago, IL. Through painting and drawing, Carlson cites entangled cultural narratives and institutional authority relating to objects based on the merit of possession and display. Her current research includes Indigenous Futurism and assimilation metaphors in film. Her work has been acquired by institutions such as the British Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the National Gallery of Canada. Carlson was a 2008 McKnight Fellow and a 2017 Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors grant recipient.

sienna broglie: What was your introduction to art?

Andrea Carlson: That’s pretty easy. My dad is a painter. All of my family, if not painting or drawing, is beading or crafting things. I know some artists had parents who wanted them to pursue a different field; who discouraged them from developing their talents. I never really experienced that. I was encouraged to make art from a very young age. It was something that I took for granted growing up. I always had good support and was lucky in that way.

sb: What mediums did you first explore?

AC: At first it was a little bit of everything. In elementary school I started painting with oil and acrylics but before that I was drawing. I started drawing to learn the rules: how to draw a human’s face or figure out human ratios and form various objects. They became a kind of language or grammar with which to render. Once the rules aren’t a challenge anymore, you want to break them enough so that what you’re making is odd or interesting; so that people can’t look away. As opposed to a fully formalized drawing of a bouquet or landscape that we’ve seen before, there has to be dissonance. The design has to frustrate the viewer in order to hold them a bit longer.

sb: You obviously have your own style.

AC: It took me a while to break all of the rules. Even now I fight some of the formal drawing tendencies that I’ve learned. Sometimes I have to sit with my own paintings and drawings for a while before they grow on me. There will be something that I hate in a piece so I’ll try to antagonize what it is that’s frustrating me while simultaneously I will like a bizarre aspect that everyone else hates so I’ll fix it just enough to let the piece remain a bit broken. I often play around with my comfort level design-wise.

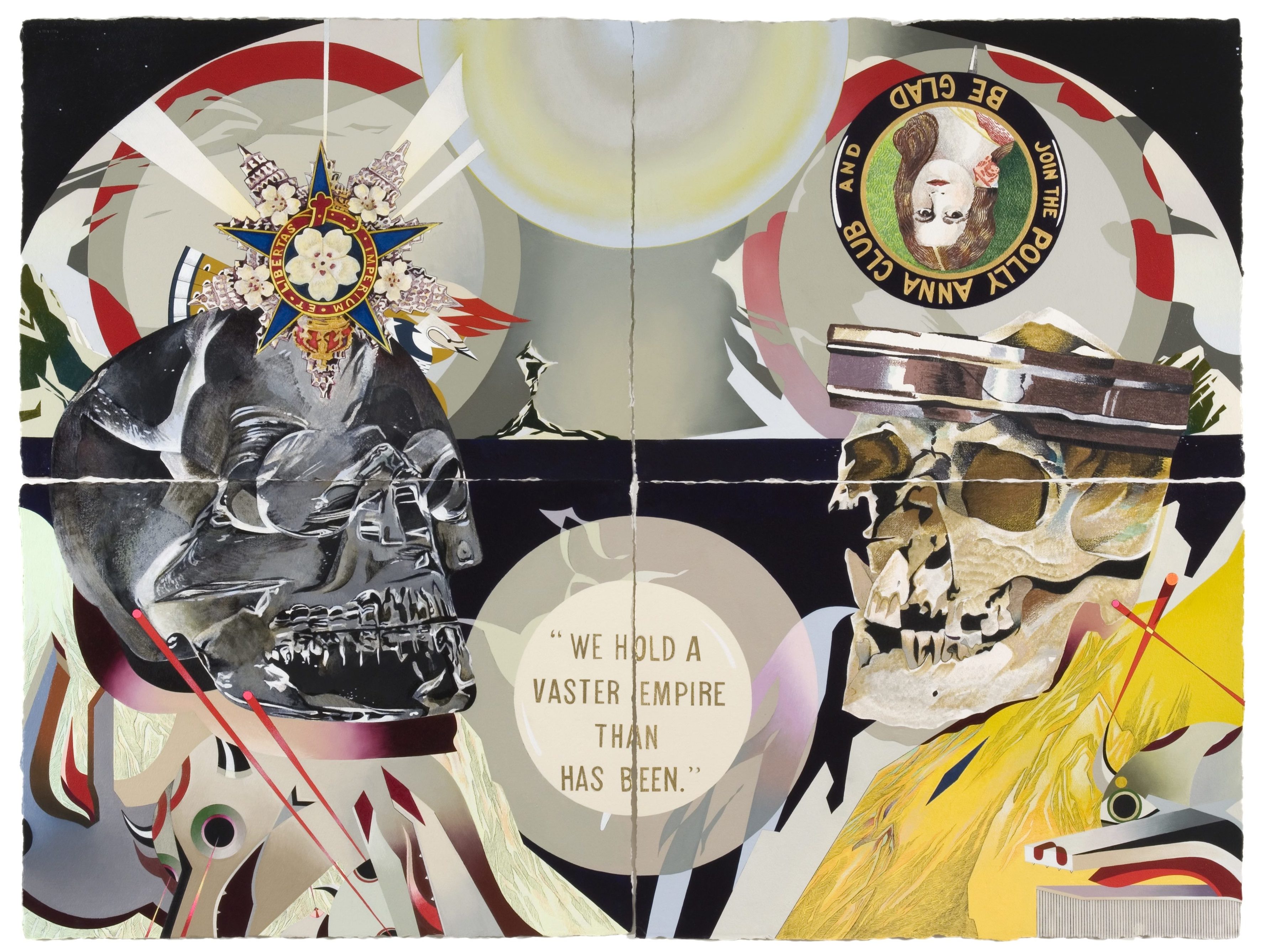

Vaster Empire, 2008, 44″ x 60″ acrylic, ink, gouache, and oil on paper.

sb: What does your process look like when you make a piece?

AC: Right now we are looking at Red Exit. This piece is 30 sheets of paper that were cut in half and stacked to make 60 cells. I divided the bottom of each cell into fifths and each element in the piece will be introduced at one fifth of the page in from its corresponding position in a cell above or below. That on-fifths rule is true in Red Exit for everything except the bat symbol. This is the sister piece to Ink Bable which had a kind of doom pig that also broke the one-fifth rules. There is a slight variance between repeated elements so that it doesn’t look like wallpaper. Instead it seems sequential or as if something will move and is able to fight the static nature of the imagery.

Each piece is hand painted. Print makers often assume that a bit is printed but realize it’s not once they get close. It wouldn’t be any easier if it were printed considering each element has a slight variance. I think it would be just as maddening.

sb: How long does a piece this large take to finish?

AC: Ink Babble took a year to finish and I have been working on this piece for quite a while. I have so many projects going on at once, it’s hard for me to tabulate how long it takes.

sb: What does your studio routine look like?

AC: Lately it’s been terrible! I would love to do a 9-5 in the studio every day. There have been times when I would do a 9-5, seven days a week. Now I am doing a lot more arts writing, traveling, and speaking about my work. All of that takes a toll on my studio practice. I should probably be a fierce protector of studio time but I also absolutely love writing and speaking about work. The writing and traveling makes it so that I won’t get burnt out in the studio. You can get burnt out on either side. I think my practice is pretty well balanced but I do crave getting in more often.

sb: Can you expand on the kaleidoscopic mirroring pattern in all of your paintings?

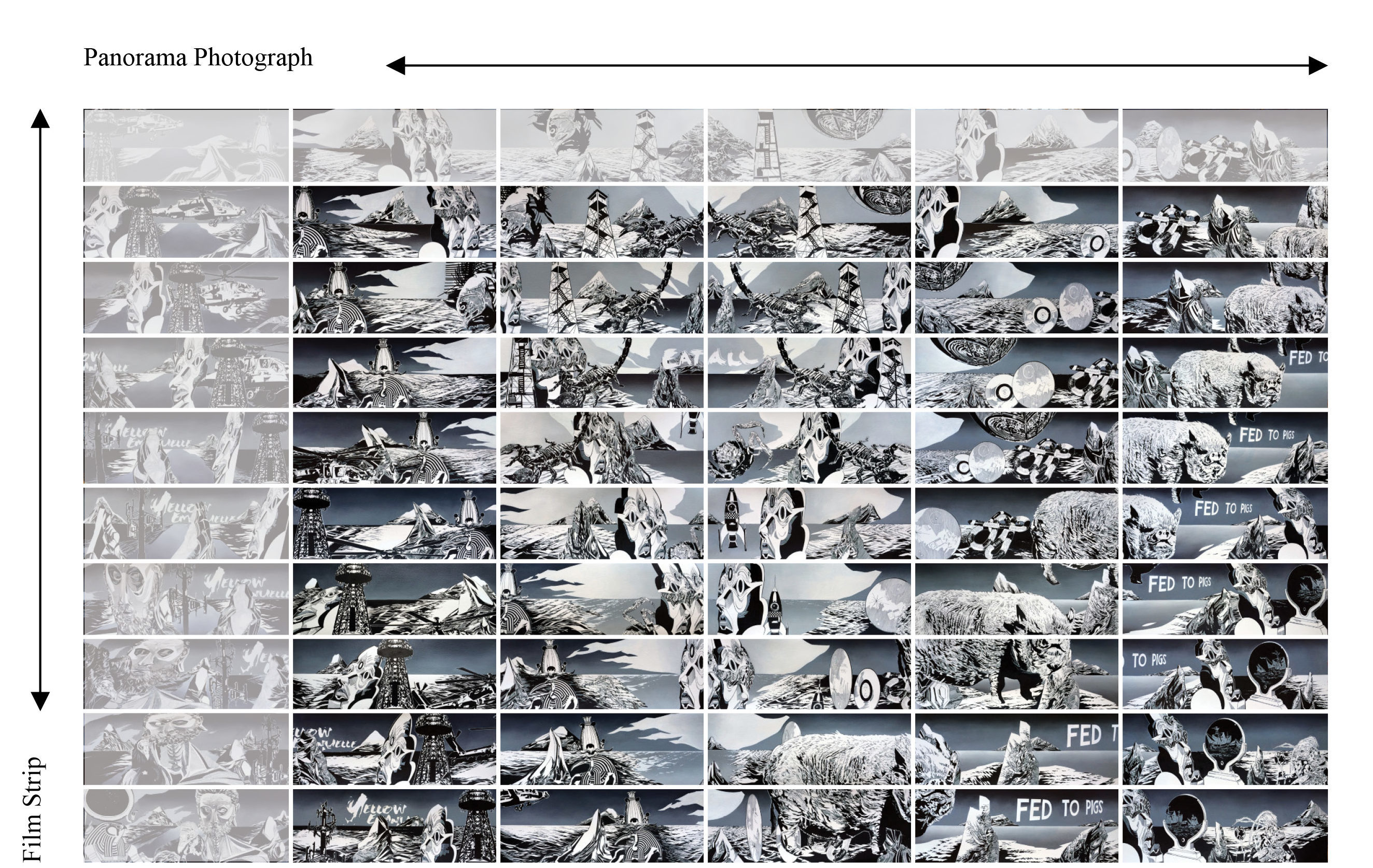

AC: So if each column was a film strip of a panorama shot taken out of a celluloid camera you would see information repeat itself at an angle from cell to cell. If each row was a still panorama shot of a landscape you would have one linear horizon line. Then across would be static space dominant (photography) and up or down would be dynamic time dominant (video.) Each piece is essentially a bifurcated panorama in two directions that together make a continuum. I was thinking about the possibilities of getting into a film and changing what was within. What would that topologically look like? This is the best I could do. That is why there is a repetition. See figure below.

INK BABLE, 2013, 10′ x 16′ ink and oil on paper. (edited diagram, 2019.) original image

sb: You mention in your bio drawing from iconography in film. Why film specifically as a media as opposed to other public media?

AC: Filmmaking is like contemporary storytelling. It can really craft how people view the world and relate to other communities; it socially forms us. I also have this curiosity surrounding movement and life in image making. I’ve always wanted to fight the static nature of my paintings. With my landscapes you move around them with your eyes and there is an inability to take them in all at once. Like films and movies they are time based; you can’t take them in all at once. The viewer is fed slowly.

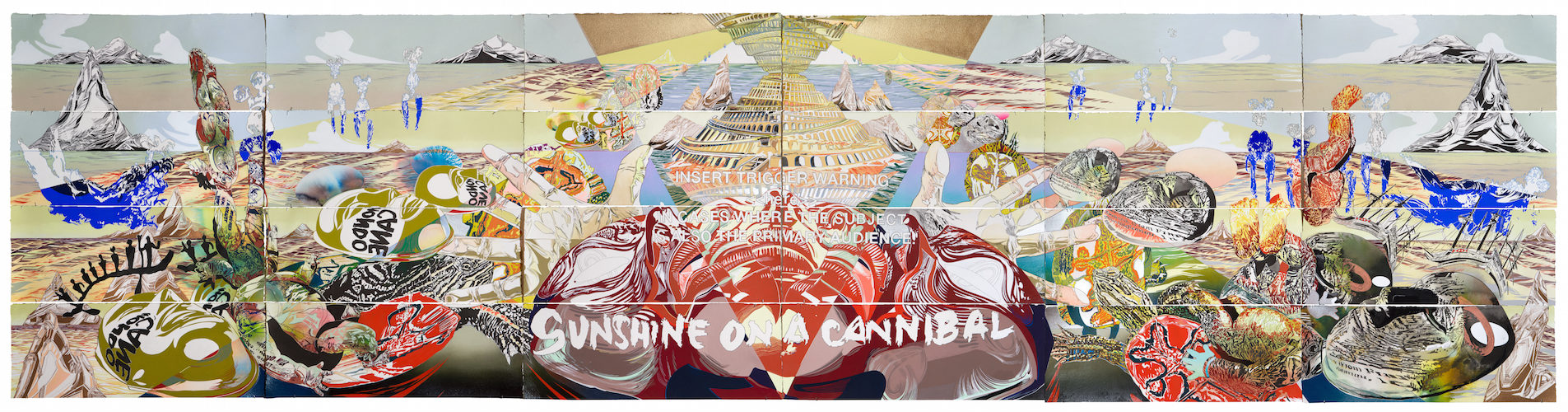

The imagery I am propagating and putting out into the world acts almost reflexively to the propaganda of film and the ways in which that has been devastating; specifically among Indigenous communities with the promotion of blood libel, accusations of cannibalism, and other gruesome stereotypes. These films, like Westerns among other genres, do not give native people a voice to speak for themselves. Sometimes I reference these harmful films in the titles of my work as a means to say “we see you.” I make a record of the wrongdoing in my work. It is almost like a gaze reversal, documenting that violent representation and incorporating it into my landscapes as a part of the story.

sb: How do you choose the symbols and iconography included in a piece? Is each piece curated individually or are the symbols curated within the greater body of work as a whole?

AC: I am like a collector of things. Often when I find something I want to include I’ll pull an image from the internet and put it in a file on my desktop. I will draw from that and curate the relationships between the material. The relationships between some of these objects will surface just by having them close. They will be in my thoughts and connections will arise naturally.

In Ink Babel I incorporated a teleprompter. I was going through a phase where I was focused on old machines that were used to disseminate or capture information. Another element I use a lot is the brown bat, they might go extinct within our lifetime, so I’ve been charmed by them.

One of the ideas behind Red Exit is celebrating Indigenous spaces or spaces that native people make for ourselves. Oftentimes we are the subject matter, people will talk about us or we will be included in someone else’s project, which is fine, but I wanted to make a piece that really just celebrates native knowledge and native spaces. Particular to this piece there is a beaded medallion that I’m going to put alongside the brown bat. When I was in the Venice Biennale, an Indigenous artist made this beaded medallion with a golden lion. It was an award to be given to an Indigenous scholar, a riff on the official Golden Lion. It is like we have to make our own because there’s no way we’ll ever be given the main stage.

The space in which we both showed our work, the Indigenous Pavillion, was a little room in a college curated by Indigenous curators who presented Indigenous artists from around the world. The pavillion was a way to break apart the state system; the post colonial sense of nationalism that the US and Canadian pavilions, among others, represented. That post colonial sense of nationalism does not include Indigenous people or, if it does, will include us within that state system, that colonial structure. The creation of the Indigenous pavilion is really clever but at the same time, Indigenous people picking Indigenous artists in a space that is outside of the main picture creates a marginalized space. As an artist we crave the main door, we don’t want the marginalized reservation space. That’s been my attitude throughout most of my career but then lately I’ve been thinking no- those marginalized spaces that we’ve made for ourselves are also really cool. My desire or aesthetic is changing when it comes to spaces and so I want this piece, Red Exit, to celebrate that.

In addition to the celebration of Indigenous spaces I also want to show the complicated nature of these spaces. Included in this piece is a cowrie shell etched with the Lord’s prayer. I don’t have any desire for Jesus or anything but I can understand how that has affected the Indigenous community. The cowrie shell is a really important object in Ojibwe spirituality so then to have the Lord’s prayer grafted onto it, what does that mean? I once had a professor who said “I can teach you about Ojibwe spirituality and Ojibwe teachings but when 85-90% of Ojibwe people are Christian, then what is authentically Ojibwe?” There is a kind of tragic commentary on the stick we are all in; there is no going back, we are always making anew. I’m picking up little pieces. Also included in this piece are mica hands and talons that overlap hands. I just can’t get them out of my head because these things were dug up all throughout Illinois and Iowa and the upper Midwest. I wonder about them: where they came from, who created them. A lot of tribes stake claims to them which leads me to wonder about Indigenous presence in the past.

Apocalypse Domani, 2012.

sb: Do you build a narrative of Indigenous futurism in your pieces?

AC: I’m starting to write a paper on this right now. There are various Indigenous philosophical traditions that mess with the Western construct of lineal time. We have this concept of Western lineal time and we have chunky landscape paintings that don’t really reflect the unity of space. Every single one of my pieces has a sea-scape with an infinite horizon line. When you look at a landscape there is no such thing as a “landscape” plural because we live on a sphere. Topologically there is just one landscape and multiples are merely cut-outs of that sphere.

I really love Indigenous Futurism and I think unfortunately for some non Native people it is a foreclosure of Indigenous histories. To understand Indigenous Futurism it is important to understand Indigenous histories and I don’t want Indigenous Futurism to end the education that everyone needs to have in those histories.

What I like is the possibility to imagine our survivals richly. When history has tried to screw us over and over again, I like the idea of speculating on future space where so many things could play out differently. We can put our desires into fiction as a space that we control. You can locate joy in that space if it is not being reflected and that is important for survival.

The human-centeredness in conversations about the Anthropocene and the end of the world is scary. Indigenous people are finally rising up and demanding changes for environments when suddenly everyone wants to declare the world almost over. We finally get to rise up and then game over? Don’t pull the rug out from under us. We still want to live, we want to fight to the bitter end. Don’t tell us it’s over, we’re not ready for it. We have already survived so many genocides and so many failed attempts at that. So yes, it is the end of the world now but it has been then end of the world 16 times over. We have felt the ends of the world and survived them in the past. So I think about that as far as how Indigenous Futurism can answer some of the Western fantasies for the future. The future is still a battleground.

sb: What are your biggest influences, artist or otherwise.

AC: That is really hard because if I start to notice an influence or if my work feels like someone else’s I quickly try to retaliate. I have a number of influences as far as philosophical work and how I order information. George Morrison was an abstract expressionist, also from Grand Portage. I would apply him as an influence because he always put a horizon line through his abstractions. It is representative of Lake Superior, where our Nation sits. He would discuss horizons as this liminal space, a forever space. Growing up on Rainy Lake and Lake Superior in Minnesota, once you see the lake a lot you get that horizon line baked into how you order information. I haven’t been able to break up with this horizon line and I think that comes from George Morrison.

I don’t know if you can count the lake as an influence, but it definitely is one. I see a lot of the objects in my work as debris that washed onto the shore. Comic books are another big influence. I love playing with line quality and have definitely leaned into the ways that inkers handle line in comics. I also love storytelling and the ways in which comics tell stories. I’ve also been influenced heavily by Japanese Anime. Those stories can be really beautiful and complex and tragic at the same time which is something I have leaned into. I haven’t yet figured out how to write compelling stories so painting will work for now.

There is a lot that is not so much inspired by influence as it is a product of my bizarre process. Some of the elements in my work are drawings that I didn’t like which got cut up and placed in a new way, leaving me to fill in information from the cutouts like a xerox copy. Then there are elements that I take for granted that I implement consistently so as not to reinvent the wheel each time. Those are sacred things that, when I’m bored in the future, will have to change.

Sunshine on a Cannibal, 2015, 44″ x 180″ acrylic, ink, and gouache on paper.

sb: Alongside your studio practice, what else are you in the midst of?

AC: I was asked to do an Indigenous read on this Anthropocene project for which a German art house named the Mississippi River the “River of the Anthropocene” because of its numerous dams and locks, the dredging and other human alterations done to it. Scientists have always named past epochs after they have occured. To name the current epoch and define it as being central to humans seems like a self defeating prophecy. We are not waiting for future generations to name this epoch because we don’t believe they’ll exist. There is not a lot of hope in humanity, in the future. Maybe that’s okay, maybe humans are a bit overrated. So I wrote an essay- that I don’t know if they will publish- titled “The Mississippi is the Opposite of the Anthropocene.” Yes, we have altered it in so many ways but there is a river in each of us. The Mississippi gives us water and all water is connected. Let’s not fool ourselves that we have more control than we actually do. In the end, water goes where it wants to go. Floods definitely humble those who think we have it all worked out. In the essay I cite a lot of the activism that Indigenous women have contributed; like Water Walks. There was a woman, Josephine Mandamin, who in 2003 carried a copper bowl of water around Lake Superior, walked the entire distance. Her act spread and later turned into the water walking movement among indigenous communities. Her niece, Autumn Pelier, spoke in front of the UN in full regalia when she was 13 years old. She gave all of these beautiful teachings about women and water and how each of us is born of our mother’s water who was born of her mother’s water so on and so on, creating an ancient river. For my essay I did some video work, thanking Indigenous women in Minneapolis and St Paul for their activism around the Mississippi River. The curriculum of this project included paddling down the Mississippi River. I did 38 miles with a group but not the whole river. The rest are still out there right now paddling.

In addition to that project, I have been writing a lot of essays. I just finished an essay for the Tlingit/Unangax̂ artist Nick Galanin and I’m in the midst of another essay on Indigenous Futurism. Typically I keep score of how many men versus women I am asked to write or speak on. Nick is a guy so now I am in debt to support three women. I keep this ratio where it has to be three to one because men are so overrepresented in the arts world. Last week I was on a panel for George Morrison’s work which again puts me in debt to three women. I was invited to speak on this man but now I should organize a panel or something that includes women. Actually that panel was a total coup and we ended up talking about women in the art world. So lately I have been doing a lot of arts writing and speaking. I absolutely love supporting other artists.

To keep up with Andrea, visit https://www.mikinaak.com